Fri, Jan 30, 2026

Volume 14, Issue 3 (9-2025)

2025, 14(3): 8-14 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Asadi Aria A, Simdar N, Hajibagheri P. Low-level Laser Therapy in Direct Pulp Capping: A Narrative Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal title 2025; 14 (3) :8-14

URL: http://3dj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-665-en.html

URL: http://3dj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-665-en.html

1- Student Research Committee, School of Anzali International Campus, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

2- Department of Endodontics, Dental Sciences Research Center, School of Dentistry, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine, Dental Sciences Research Center, School of Dentistry, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,hajibagheripedram@gmail.com

2- Department of Endodontics, Dental Sciences Research Center, School of Dentistry, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine, Dental Sciences Research Center, School of Dentistry, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 575 kb]

(63 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (217 Views)

Full-Text: (5 Views)

1. Introduction

Pulp capping is a dental procedure aimed at preserving the vitality of the tooth’s pulp after it has been exposed or nearly exposed due to injury or deep cavity preparation. This technique involves placing a dental biomaterial directly over the exposed or nearly exposed pulp tissue to promote healing. This process also stimulates the formation of a mineralized tissue barrier, which protects the pulp from infection and further damage (1-3).

The concept of pulp capping dates back to 1756, with early materials used empirically and often based on misconceptions about pulp healing. As the role of microorganisms became understood, disinfecting but frequently cytotoxic agents were adopted. Scientific evaluation began in the early 20th century, culminating in Hermann’s introduction of calcium hydroxide, which became the gold standard due to its biocompatibility (4, 5).

In recent decades, advances in material science have produced newer pulp-capping agents with superior biocompatibility and improved clinical outcomes compared to calcium hydroxide (6-8). Currently, pulp capping is recognized as a vital procedure for preserving tooth vitality, with ongoing research focused on optimizing materials and techniques to enhance healing and long-term success (2, 9).

There are two main types of pulp capping procedures: Direct and indirect pulp capping (10, 11). Direct pulp capping (DPC) is performed when the dental pulp is exposed, and a biocompatible material is placed directly over the exposure to preserve pulp vitality and stimulate dentin formation (7, 11). Indirect pulp capping is used when the pulp is nearly exposed but not visible; a thin layer of softened dentin is left to avoid exposure, and a protective material is placed over it to encourage healing (11, 12).

The most commonly used materials for DPC include calcium hydroxide, mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA), and newer calcium silicate-based materials, such as biodentine and tricalcium silicate cements (13-16). Recent studies have also explored the use of nano-hydroxyapatite and adhesive resin systems, though adhesive systems generally show lower success rates than traditional materials (16-18). The choice of technique and material is influenced by factors, such as the nature of the pulp exposure, the degree of inflammation, and the clinician’s preference (19).

Research indicates that the use of laser therapy as an adjunct to direct dental pulp capping can enhance healing outcomes and improve the procedure’s prognosis. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses show that teeth treated with laser therapy during DPC have significantly higher success rates and lower clinical or radiologic failure rates than with conventional methods, with odds ratios and risk ratios favoring laser-assisted treatments (20-22).

Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) appears to reduce inflammation, promote reparative dentin formation, and improve odontoblast organization, as demonstrated in animal studies using bioceramic materials, such as endosequence root repair material (23, 24). In vitro studies further suggest that combining LLLT with dental capping agents increases the viability and proliferation of apical papilla stem cells, which are important for dental tissue regeneration.

The biological effects of photobiomodulation depend on laser parameters, such as wavelength and energy, because different cellular chromophores absorb specific wavelengths, initiating mitochondrial photochemical reactions that enhance ATP synthesis and activate cell signaling pathways regulating proliferation and differentiation (25).

With continuous improvements in laser technology leading to enhanced energy delivery and biological performance, an updated evaluation of LLLT is required. This narrative review focuses exclusively on recent randomized controlled trials of LLLT-assisted DPC to clarify how laser parameters and capping materials influence clinical, radiographic, and histological outcomes. However, this area remains underdefined in the current literature.

2. Materials and Methods

This narrative review was undertaken to explore and synthesize emerging evidence on the adjunctive use of LLLT in DPC procedures, with a particular focus on randomized clinical trials (RCTs). The review followed a flexible, interpretive approach typical of narrative reviews, emphasizing qualitative integration of findings while maintaining transparency and methodological clarity.

A comprehensive literature search was performed in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar from database inception to November 2025. The search strategy combined controlled vocabulary and free-text terms, including: (“low-level laser therapy” OR “LLLT” OR “photobiomodulation” OR “diode laser”) AND (“direct pulp capping” OR “DPC” OR “vital pulp therapy” OR “pulp exposure” OR “dentin bridge”) AND (“randomized controlled trial” OR “RCT”). The search was limited to English-language human studies. The reference lists of relevant articles were also manually examined to identify additional publications of interest. Manual checking of database results ensured that studies potentially overlooked by automated searches were captured for consideration.

Studies were considered for inclusion if they involved human subjects undergoing DPC due to carious pulp exposure, where LLLT was applied as an adjunct to capping materials and compared with conventional DPC performed without laser use. Eligible studies were expected to report at least one relevant clinical, radiographic, or histological outcome—such as treatment success, postoperative pain, dentin bridge formation, or pulp tissue characteristics—and to be designed as RCTs.

Studies were excluded if they focused on pulpotomy or indirect pulp capping procedures, employed high-power lasers for cutting or coagulation, or used non-RCT formats, such as animal experiments, literature reviews, or case reports. Articles were also excluded if they lacked sufficient methodological details or LLLT parameters, presented no measurable outcomes, were not published in English, or were unavailable in full text.

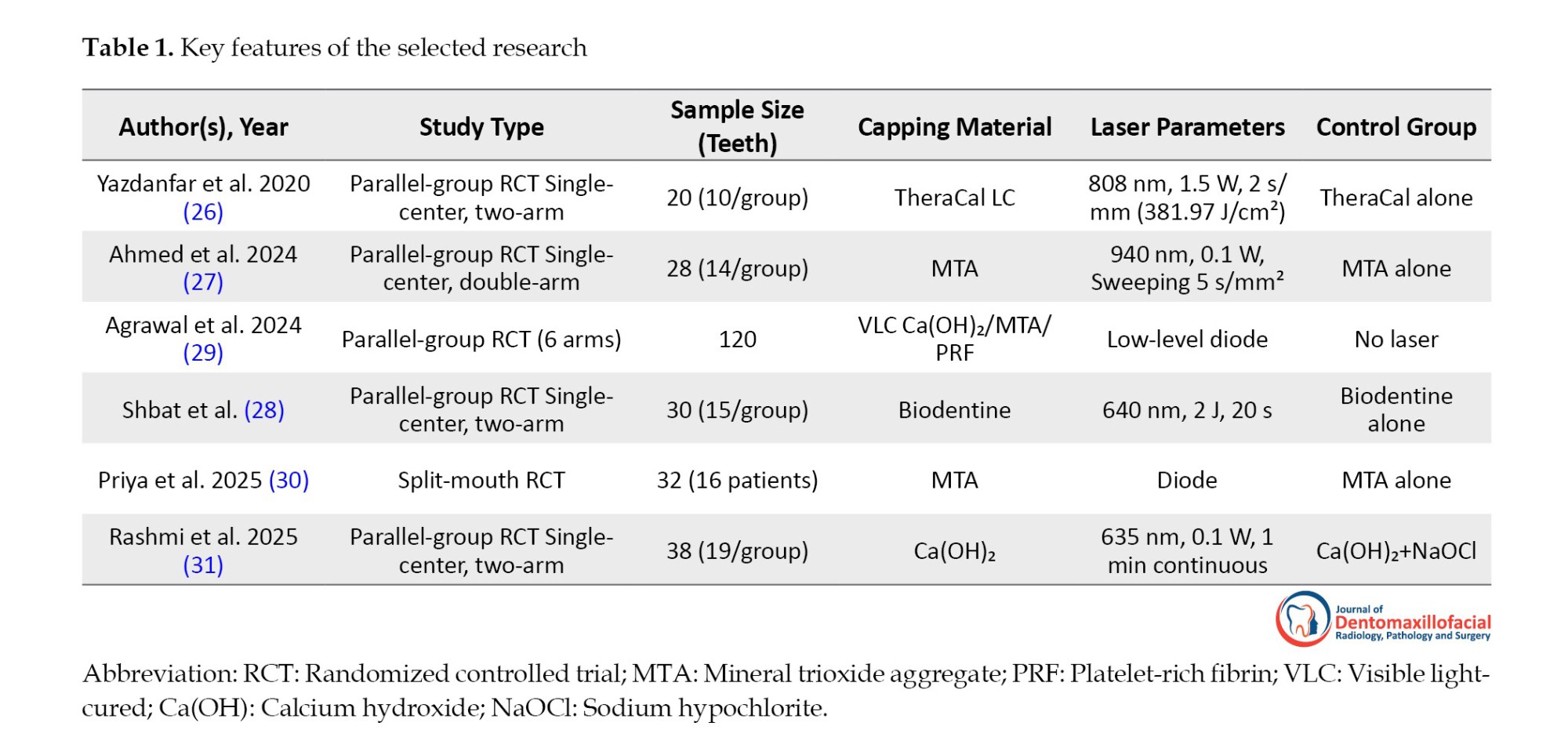

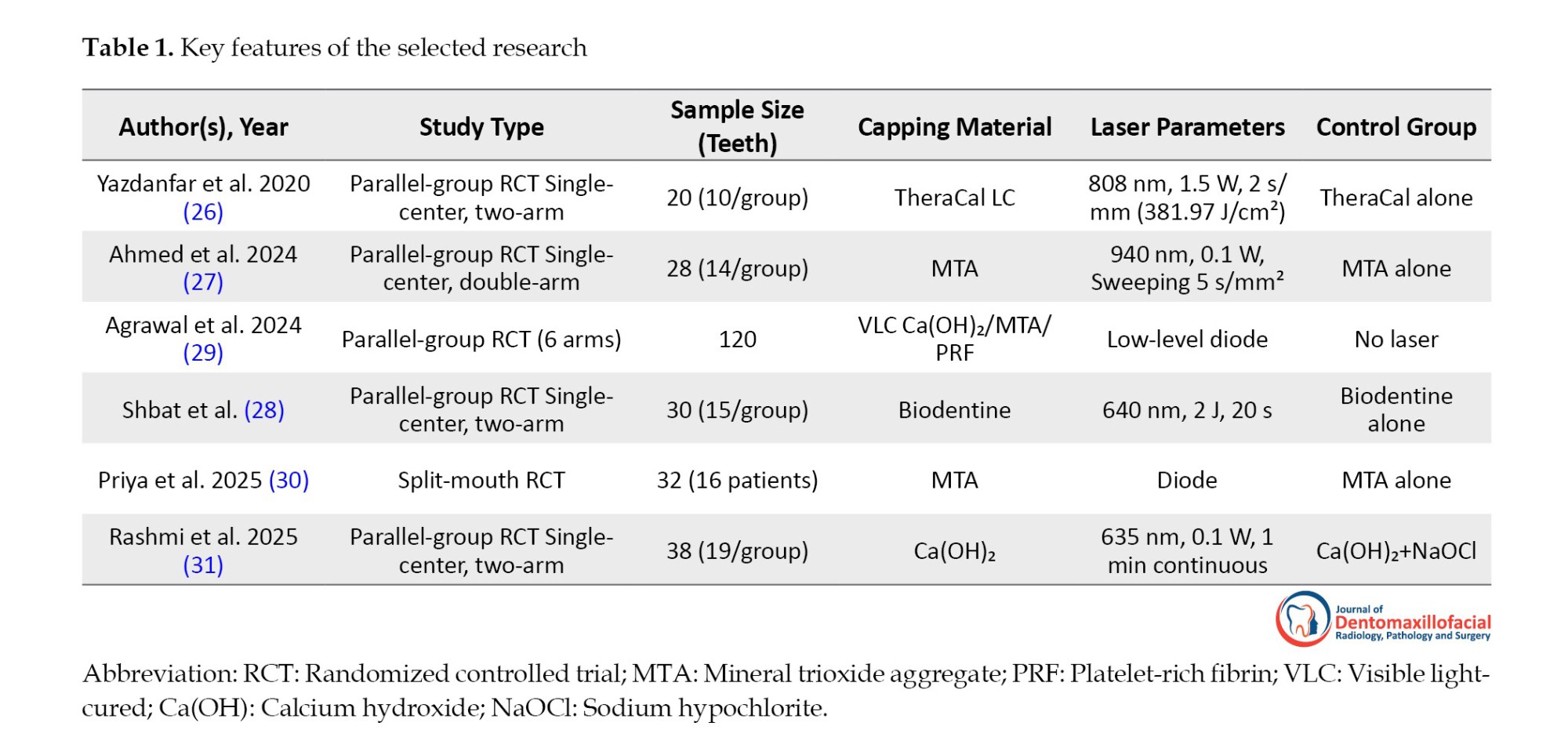

Relevant information from each included article was extracted descriptively, emphasizing publication details (author, year), study design (parallel-group or split-mouth, randomization, blinding), sample characteristics (number and type of teeth), laser parameters (wavelength, power, duration, mode, energy density, and application technique), type of capping material, and reported outcomes. These details were organized into a summary table (Table 1) to facilitate comparison and synthesis.

The findings were synthesized narratively, with studies grouped by outcome domains, such as clinical success, dentin bridge formation, postoperative pain, and histological quality. Emphasis was placed on identifying conceptual patterns and methodological nuances across different laser parameters and capping materials. No statistical pooling or meta-analytic procedures were performed, as the aim was to provide a qualitative, interpretive understanding of the literature rather than a quantitative summary.

Artificial intelligence tools (specifically Grok 4, xAI) were used exclusively for linguistic refinement—enhancing grammar, sentence structure, and stylistic consistency—without influencing data interpretation or analysis.

3. Results

A literature search yielded a range of publications addressing the use of LLLT in DPC. Following a detailed examination of the retrieved literature, only a limited number of studies have directly investigated the adjunctive use of LLLT within clinical DPC contexts. After evaluating the relevance and the content of these studies, six publications were identified as conceptually aligned with the focus of this review and were therefore included in the narrative synthesis (26-31).

Yazdanfar et al. (2020) applied an 808 nm diode laser at 1.5 W (381.97 J/cm²) prior to TheraCal LC capping in 20 teeth, finding clinically superior outcomes in the laser group (P<0.001) with no radiographic difference (P=0.56) and maximum dentin bridge thickness of 0.40 mm at one month in both groups (26). Similarly, Ahmed et al. (2024) used a 940 nm diode laser at 0.1 W (sweeping 5 s/mm²) before MTA in 28 molars, reporting 100% clinical success in both groups and significantly thicker dentin bridge in the laser group (0.443 mm vs 0.411 mm at 12 months, P=0.046), with equivalent short-term results (27).

Expanding on laser-assisted biostimulation, Agrawal et al. (2024) tested low-level diode laser combined with visible light-cured (VLC) calcium hydroxide (Ca[OH]), MTA, and platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) in 120 teeth, observing that the MTA+PRF+laser group produced the thickest dentin bridge with statistically significant differences in thickness across groups (29). In a related application, Shbat et al. (2025) delivered a 640 nm diode laser (2 J, 20 s) before Biodentine in 30 immature first molars, demonstrating faster apical development, improved apex maturation, and significantly better pain relief in the laser group compared to Biodentine alone (28).

MTA remains the reference standard for DPC due to its superior biocompatibility and bioactivity, though its long setting time and potential for discoloration may limit its clinical practicality. Biodentine, with its faster setting and improved handling, achieves comparable dentin bridge formation, making it suitable for cases requiring immediate restoration. TheraCal LC, a light-cured resin-modified calcium silicate, offers convenient application and immediate setting but exhibits reduced calcium ion release and bioactivity compared with pure hydraulic materials. When combined with LLLT, these materials may demonstrate enhanced odontogenic differentiation and dentin bridge formation; however, this interaction depends on each material’s optical absorption and hydration properties. Hydrophilic materials such as MTA and Biodentine show greater compatibility with laser-induced photobiomodulation than resin-based alternatives, such as TheraCal LC (26, 32).

Further supporting histological benefits, Priya et al. (2025) applied low-level diode laser before MTA in 32 premolars, revealing complete dentin bridges in 87.5% of the laser group vs 68.8% in control, >0.25 mm thickness in 81.3% vs 68.8%, and reduced inflammation (P<0.05) with more uniform, thicker bridges in the laser group (30). Similarly, Rashmi et al. (2025) used a 635 nm diode laser at 0.1 W for 1 minute before Ca(OH)₂ in 38 molars, achieving 90% clinical success in the laser group vs. 80% in the control group (Ca[OH]+sodium hypochlorite [NaOCl]). However, the difference was not statistically significant (31).

Wavelength may influence how each laser interacts with dental tissues, as different wavelengths exhibit distinct absorption profiles, penetration depths, and thermal behaviors (22).

4. Discussion

Most included RCTs reported the efficacy of LLLT as an adjunct in DPC of permanent teeth (26-31). Across studies involving 268 teeth, LLLT appears to enhance clinical outcomes and is associated with thicker and more uniform dentin bridge formation, and reduced pulpal inflammation. Ahmed et al. (27) and Priya et al. (30) provided robust clinical and histological evidence, with the laser group achieving greater dentin bridge thickness and higher complete bridge rates, respectively. These findings align with the primary objective of this review—to evaluate LLLT as a biostimulatory modality in DPC—and confirm its supportive role in preserving pulp vitality and accelerating reparative dentinogenesis.

Substantial heterogeneity in laser parameters exists across the studies. The wavelengths ranged from 635 nm (31) to 940 nm (27), with power outputs varying from 0.1 W (27, 31) to 1.5 W (26) and energy deliveries from 2 J (28) to 381.97 J/cm² (26). Despite this diversity, LLLT proved effective alongside multiple capping agents, including MTA (27, 31), TheraCal LC (26), Biodentine (28), Ca(OH)₂ (31), and PRF combinations (29). The strongest outcomes emerged with MTA and MTA+PRF, yet the absence of a standardized LLLT protocol limits inter-study comparability and underscores the need for future dose-optimization research. In addition, variability in laser parameters (energy, duration) likely contributed to the differences in outcomes across studies.

Radiographic and histological endpoints revealed targeted benefits of LLLT. Ahmed et al. (27) documented increased dentin bridge thickness at 12 months, while Priya et al. (30) reported superior bridge completeness, thickness, and reduced inflammation. In immature teeth, Shbat et al. (28) observed accelerated apical development and apex maturation along with marked pain reduction. Agrawal et al. (29) highlighted synergistic effects when LLLT was combined with PRF and MTA, yielding the thickest reparative dentin. These outcomes likely stem from LLLT’s documented anti-inflammatory effects and its ability to stimulate the proliferation of dental pulp stem cells, mechanisms reported in the literature (33, 34).

The advantages of LLLT in enhancing dentin bridge quality and clinical predictability suggest a viable pathway for integrating this modality into routine DPC protocols, particularly with calcium silicate-based materials, such as MTA and Biodentine (26-28). The non-invasive nature of LLLT, coupled with its ability to mitigate postoperative pain (28) and improve reparative outcomes even in challenging immature teeth, makes it a valuable adjunct for preserving pulp vitality in deep caries management. Clinicians may consider LLLT especially in cases where hemostasis and biostimulation are critical, though material-specific synergies—such as the superior bridge formation with MTA+PRF combinations (29) warrant tailored application.

Variability in laser parameters across the included studies likely contributed to differences in clinical outcomes, which should be considered when interpreting the evidence. The diode lasers used in the trials demonstrated substantial heterogeneity in wavelength, output power, exposure time, and energy density—ranging from high-energy applications, such as 808 nm at 1.5 W for 2 s/mm (381.97 J/cm²) (26), to very low-power protocols such as 940 nm at 0.1 W with sweeping irradiation (27), or 635–640 nm low-level laser settings delivered over longer durations (28, 31). Studies employing diode irradiation without detailed standardization or clarity in parameters further compound this variability (29, 30). These differences in irradiation characteristics may influence tissue response, biomaterial interactions, and, ultimately, the success of vital pulp therapy.

The limited evidence base constrains this review—only six RCTs were eligible—and small sample sizes in most trials (e.g. 20 teeth in Yazdanfar et al. (26); 28 teeth in Ahmed et al. (27). Follow-up periods were generally short, with long-term survival data lacking. Protocol heterogeneity in laser parameters, capping materials, and tooth maturity further complicates synthesis. Future high-quality, large-scale RCTs are essential to standardize LLLT dosimetry, establish optimal therapeutic windows, extend follow-up beyond 1–2 years to assess long-term tooth survival, and directly compare LLLT with alternative adjunctive modalities in DPC.

Previous systematic reviews have similarly highlighted the potential of lasers to enhance the outcomes of DPC, noting improved clinical success but also emphasizing the presence of confounding variables that may limit the certainty of their conclusions (22). Another meta-analysis reported that DPC achieved superior clinical results when combined with laser therapy compared with conventional approaches. In alignment with these findings, the present narrative review—drawing on six recent RCTs—supports LLLT as a promising biostimulatory adjunct in DPC (22). It is important to note that the relatively small sample size of the included RCTs limits the strength of the current evidence and should be considered when interpreting the results. A key strength of this review is its exclusive focus on randomized controlled trials, ensuring that the conclusions regarding the effects of LLLT on DPC are based on the highest level of clinical evidence.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the synthesized evidence from these six RCTs suggests that LLLT may be a promising biostimulatory tool in DPC, with potential benefits across diverse laser parameters and capping agents. While current findings are encouraging, the field remains in an exploratory phase due to methodological variability and limited long-term data. To advance clinical adoption, future investigations should prioritize larger multicenter trials, and extended follow-up to definitively establish its role in vital pulp therapy. A standardized laser protocol would make future research more comparable.

Ethical Considerations

This review used publicly available data, with proper citations, and required no ethics approval because no human subjects were involved.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' Contributions

Arah Asadi Aria: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing Narges Simdar: Review & Editing, Original Draft Pedram Hajibagheri: Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Availability of Data and Material

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran, for its support of this work.

References

Pulp capping is a dental procedure aimed at preserving the vitality of the tooth’s pulp after it has been exposed or nearly exposed due to injury or deep cavity preparation. This technique involves placing a dental biomaterial directly over the exposed or nearly exposed pulp tissue to promote healing. This process also stimulates the formation of a mineralized tissue barrier, which protects the pulp from infection and further damage (1-3).

The concept of pulp capping dates back to 1756, with early materials used empirically and often based on misconceptions about pulp healing. As the role of microorganisms became understood, disinfecting but frequently cytotoxic agents were adopted. Scientific evaluation began in the early 20th century, culminating in Hermann’s introduction of calcium hydroxide, which became the gold standard due to its biocompatibility (4, 5).

In recent decades, advances in material science have produced newer pulp-capping agents with superior biocompatibility and improved clinical outcomes compared to calcium hydroxide (6-8). Currently, pulp capping is recognized as a vital procedure for preserving tooth vitality, with ongoing research focused on optimizing materials and techniques to enhance healing and long-term success (2, 9).

There are two main types of pulp capping procedures: Direct and indirect pulp capping (10, 11). Direct pulp capping (DPC) is performed when the dental pulp is exposed, and a biocompatible material is placed directly over the exposure to preserve pulp vitality and stimulate dentin formation (7, 11). Indirect pulp capping is used when the pulp is nearly exposed but not visible; a thin layer of softened dentin is left to avoid exposure, and a protective material is placed over it to encourage healing (11, 12).

The most commonly used materials for DPC include calcium hydroxide, mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA), and newer calcium silicate-based materials, such as biodentine and tricalcium silicate cements (13-16). Recent studies have also explored the use of nano-hydroxyapatite and adhesive resin systems, though adhesive systems generally show lower success rates than traditional materials (16-18). The choice of technique and material is influenced by factors, such as the nature of the pulp exposure, the degree of inflammation, and the clinician’s preference (19).

Research indicates that the use of laser therapy as an adjunct to direct dental pulp capping can enhance healing outcomes and improve the procedure’s prognosis. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses show that teeth treated with laser therapy during DPC have significantly higher success rates and lower clinical or radiologic failure rates than with conventional methods, with odds ratios and risk ratios favoring laser-assisted treatments (20-22).

Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) appears to reduce inflammation, promote reparative dentin formation, and improve odontoblast organization, as demonstrated in animal studies using bioceramic materials, such as endosequence root repair material (23, 24). In vitro studies further suggest that combining LLLT with dental capping agents increases the viability and proliferation of apical papilla stem cells, which are important for dental tissue regeneration.

The biological effects of photobiomodulation depend on laser parameters, such as wavelength and energy, because different cellular chromophores absorb specific wavelengths, initiating mitochondrial photochemical reactions that enhance ATP synthesis and activate cell signaling pathways regulating proliferation and differentiation (25).

With continuous improvements in laser technology leading to enhanced energy delivery and biological performance, an updated evaluation of LLLT is required. This narrative review focuses exclusively on recent randomized controlled trials of LLLT-assisted DPC to clarify how laser parameters and capping materials influence clinical, radiographic, and histological outcomes. However, this area remains underdefined in the current literature.

2. Materials and Methods

This narrative review was undertaken to explore and synthesize emerging evidence on the adjunctive use of LLLT in DPC procedures, with a particular focus on randomized clinical trials (RCTs). The review followed a flexible, interpretive approach typical of narrative reviews, emphasizing qualitative integration of findings while maintaining transparency and methodological clarity.

A comprehensive literature search was performed in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar from database inception to November 2025. The search strategy combined controlled vocabulary and free-text terms, including: (“low-level laser therapy” OR “LLLT” OR “photobiomodulation” OR “diode laser”) AND (“direct pulp capping” OR “DPC” OR “vital pulp therapy” OR “pulp exposure” OR “dentin bridge”) AND (“randomized controlled trial” OR “RCT”). The search was limited to English-language human studies. The reference lists of relevant articles were also manually examined to identify additional publications of interest. Manual checking of database results ensured that studies potentially overlooked by automated searches were captured for consideration.

Studies were considered for inclusion if they involved human subjects undergoing DPC due to carious pulp exposure, where LLLT was applied as an adjunct to capping materials and compared with conventional DPC performed without laser use. Eligible studies were expected to report at least one relevant clinical, radiographic, or histological outcome—such as treatment success, postoperative pain, dentin bridge formation, or pulp tissue characteristics—and to be designed as RCTs.

Studies were excluded if they focused on pulpotomy or indirect pulp capping procedures, employed high-power lasers for cutting or coagulation, or used non-RCT formats, such as animal experiments, literature reviews, or case reports. Articles were also excluded if they lacked sufficient methodological details or LLLT parameters, presented no measurable outcomes, were not published in English, or were unavailable in full text.

Relevant information from each included article was extracted descriptively, emphasizing publication details (author, year), study design (parallel-group or split-mouth, randomization, blinding), sample characteristics (number and type of teeth), laser parameters (wavelength, power, duration, mode, energy density, and application technique), type of capping material, and reported outcomes. These details were organized into a summary table (Table 1) to facilitate comparison and synthesis.

The findings were synthesized narratively, with studies grouped by outcome domains, such as clinical success, dentin bridge formation, postoperative pain, and histological quality. Emphasis was placed on identifying conceptual patterns and methodological nuances across different laser parameters and capping materials. No statistical pooling or meta-analytic procedures were performed, as the aim was to provide a qualitative, interpretive understanding of the literature rather than a quantitative summary.

Artificial intelligence tools (specifically Grok 4, xAI) were used exclusively for linguistic refinement—enhancing grammar, sentence structure, and stylistic consistency—without influencing data interpretation or analysis.

3. Results

A literature search yielded a range of publications addressing the use of LLLT in DPC. Following a detailed examination of the retrieved literature, only a limited number of studies have directly investigated the adjunctive use of LLLT within clinical DPC contexts. After evaluating the relevance and the content of these studies, six publications were identified as conceptually aligned with the focus of this review and were therefore included in the narrative synthesis (26-31).

Yazdanfar et al. (2020) applied an 808 nm diode laser at 1.5 W (381.97 J/cm²) prior to TheraCal LC capping in 20 teeth, finding clinically superior outcomes in the laser group (P<0.001) with no radiographic difference (P=0.56) and maximum dentin bridge thickness of 0.40 mm at one month in both groups (26). Similarly, Ahmed et al. (2024) used a 940 nm diode laser at 0.1 W (sweeping 5 s/mm²) before MTA in 28 molars, reporting 100% clinical success in both groups and significantly thicker dentin bridge in the laser group (0.443 mm vs 0.411 mm at 12 months, P=0.046), with equivalent short-term results (27).

Expanding on laser-assisted biostimulation, Agrawal et al. (2024) tested low-level diode laser combined with visible light-cured (VLC) calcium hydroxide (Ca[OH]), MTA, and platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) in 120 teeth, observing that the MTA+PRF+laser group produced the thickest dentin bridge with statistically significant differences in thickness across groups (29). In a related application, Shbat et al. (2025) delivered a 640 nm diode laser (2 J, 20 s) before Biodentine in 30 immature first molars, demonstrating faster apical development, improved apex maturation, and significantly better pain relief in the laser group compared to Biodentine alone (28).

MTA remains the reference standard for DPC due to its superior biocompatibility and bioactivity, though its long setting time and potential for discoloration may limit its clinical practicality. Biodentine, with its faster setting and improved handling, achieves comparable dentin bridge formation, making it suitable for cases requiring immediate restoration. TheraCal LC, a light-cured resin-modified calcium silicate, offers convenient application and immediate setting but exhibits reduced calcium ion release and bioactivity compared with pure hydraulic materials. When combined with LLLT, these materials may demonstrate enhanced odontogenic differentiation and dentin bridge formation; however, this interaction depends on each material’s optical absorption and hydration properties. Hydrophilic materials such as MTA and Biodentine show greater compatibility with laser-induced photobiomodulation than resin-based alternatives, such as TheraCal LC (26, 32).

Further supporting histological benefits, Priya et al. (2025) applied low-level diode laser before MTA in 32 premolars, revealing complete dentin bridges in 87.5% of the laser group vs 68.8% in control, >0.25 mm thickness in 81.3% vs 68.8%, and reduced inflammation (P<0.05) with more uniform, thicker bridges in the laser group (30). Similarly, Rashmi et al. (2025) used a 635 nm diode laser at 0.1 W for 1 minute before Ca(OH)₂ in 38 molars, achieving 90% clinical success in the laser group vs. 80% in the control group (Ca[OH]+sodium hypochlorite [NaOCl]). However, the difference was not statistically significant (31).

Wavelength may influence how each laser interacts with dental tissues, as different wavelengths exhibit distinct absorption profiles, penetration depths, and thermal behaviors (22).

4. Discussion

Most included RCTs reported the efficacy of LLLT as an adjunct in DPC of permanent teeth (26-31). Across studies involving 268 teeth, LLLT appears to enhance clinical outcomes and is associated with thicker and more uniform dentin bridge formation, and reduced pulpal inflammation. Ahmed et al. (27) and Priya et al. (30) provided robust clinical and histological evidence, with the laser group achieving greater dentin bridge thickness and higher complete bridge rates, respectively. These findings align with the primary objective of this review—to evaluate LLLT as a biostimulatory modality in DPC—and confirm its supportive role in preserving pulp vitality and accelerating reparative dentinogenesis.

Substantial heterogeneity in laser parameters exists across the studies. The wavelengths ranged from 635 nm (31) to 940 nm (27), with power outputs varying from 0.1 W (27, 31) to 1.5 W (26) and energy deliveries from 2 J (28) to 381.97 J/cm² (26). Despite this diversity, LLLT proved effective alongside multiple capping agents, including MTA (27, 31), TheraCal LC (26), Biodentine (28), Ca(OH)₂ (31), and PRF combinations (29). The strongest outcomes emerged with MTA and MTA+PRF, yet the absence of a standardized LLLT protocol limits inter-study comparability and underscores the need for future dose-optimization research. In addition, variability in laser parameters (energy, duration) likely contributed to the differences in outcomes across studies.

Radiographic and histological endpoints revealed targeted benefits of LLLT. Ahmed et al. (27) documented increased dentin bridge thickness at 12 months, while Priya et al. (30) reported superior bridge completeness, thickness, and reduced inflammation. In immature teeth, Shbat et al. (28) observed accelerated apical development and apex maturation along with marked pain reduction. Agrawal et al. (29) highlighted synergistic effects when LLLT was combined with PRF and MTA, yielding the thickest reparative dentin. These outcomes likely stem from LLLT’s documented anti-inflammatory effects and its ability to stimulate the proliferation of dental pulp stem cells, mechanisms reported in the literature (33, 34).

The advantages of LLLT in enhancing dentin bridge quality and clinical predictability suggest a viable pathway for integrating this modality into routine DPC protocols, particularly with calcium silicate-based materials, such as MTA and Biodentine (26-28). The non-invasive nature of LLLT, coupled with its ability to mitigate postoperative pain (28) and improve reparative outcomes even in challenging immature teeth, makes it a valuable adjunct for preserving pulp vitality in deep caries management. Clinicians may consider LLLT especially in cases where hemostasis and biostimulation are critical, though material-specific synergies—such as the superior bridge formation with MTA+PRF combinations (29) warrant tailored application.

Variability in laser parameters across the included studies likely contributed to differences in clinical outcomes, which should be considered when interpreting the evidence. The diode lasers used in the trials demonstrated substantial heterogeneity in wavelength, output power, exposure time, and energy density—ranging from high-energy applications, such as 808 nm at 1.5 W for 2 s/mm (381.97 J/cm²) (26), to very low-power protocols such as 940 nm at 0.1 W with sweeping irradiation (27), or 635–640 nm low-level laser settings delivered over longer durations (28, 31). Studies employing diode irradiation without detailed standardization or clarity in parameters further compound this variability (29, 30). These differences in irradiation characteristics may influence tissue response, biomaterial interactions, and, ultimately, the success of vital pulp therapy.

The limited evidence base constrains this review—only six RCTs were eligible—and small sample sizes in most trials (e.g. 20 teeth in Yazdanfar et al. (26); 28 teeth in Ahmed et al. (27). Follow-up periods were generally short, with long-term survival data lacking. Protocol heterogeneity in laser parameters, capping materials, and tooth maturity further complicates synthesis. Future high-quality, large-scale RCTs are essential to standardize LLLT dosimetry, establish optimal therapeutic windows, extend follow-up beyond 1–2 years to assess long-term tooth survival, and directly compare LLLT with alternative adjunctive modalities in DPC.

Previous systematic reviews have similarly highlighted the potential of lasers to enhance the outcomes of DPC, noting improved clinical success but also emphasizing the presence of confounding variables that may limit the certainty of their conclusions (22). Another meta-analysis reported that DPC achieved superior clinical results when combined with laser therapy compared with conventional approaches. In alignment with these findings, the present narrative review—drawing on six recent RCTs—supports LLLT as a promising biostimulatory adjunct in DPC (22). It is important to note that the relatively small sample size of the included RCTs limits the strength of the current evidence and should be considered when interpreting the results. A key strength of this review is its exclusive focus on randomized controlled trials, ensuring that the conclusions regarding the effects of LLLT on DPC are based on the highest level of clinical evidence.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the synthesized evidence from these six RCTs suggests that LLLT may be a promising biostimulatory tool in DPC, with potential benefits across diverse laser parameters and capping agents. While current findings are encouraging, the field remains in an exploratory phase due to methodological variability and limited long-term data. To advance clinical adoption, future investigations should prioritize larger multicenter trials, and extended follow-up to definitively establish its role in vital pulp therapy. A standardized laser protocol would make future research more comparable.

Ethical Considerations

This review used publicly available data, with proper citations, and required no ethics approval because no human subjects were involved.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' Contributions

Arah Asadi Aria: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing Narges Simdar: Review & Editing, Original Draft Pedram Hajibagheri: Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Availability of Data and Material

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran, for its support of this work.

References

- Islam R, Islam MRR, Tanaka T, Alam MK, Ahmed HMA, Sano H. Direct pulp capping procedures-evidence and practice. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2023; 59:48-61. [DOI:10.1016/j.jdsr.2023.02.002] [PMID]

- Bharathisuma R, Nagireddy V, Shekar M, Nallagatla VK, Kumar S, Sunilkumar S. Pulp capping agents in operative dentistry: An updated review. Yemeni J Med Sci. 2025. [DOI:10.20428/yjms.v19i7.3029]

- Forrai J, Spielman A. History of pulp capping. Kaleidoscope history. Kaleidoscope. 2024; 14(28):428-30. [DOI:10.17107/KH.2024.28.35]

- Dammaschke T. The history of direct pulp capping. J Hist Dent. 2008; 56(1):9-23. [PMID]

- Dhaimy S, Hoummadi A, Nadifi S. Dental pulp capping a literature review. J Clin Mol Pathol. 2019; 3(1):20. [Link]

- da Rosa WLO, Cocco AR, Silva TMD, Mesquita LC, Galarça AD, Silva AFD, et al. Current trends and future perspectives of dental pulp capping materials: A systematic review. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2018; 106(3):1358-68. [DOI:10.1002/jbm.b.33934] [PMID]

- Kunert M, Lukomska-Szymanska M. Bio-inductive materials in direct and indirect pulp capping-A review article. Materials. 2020; 13(5):1204. [DOI:10.3390/ma13051204] [PMID]

- Gomez-Sosa JF, Granone-Ricella M, Rosciano-Alvarez M, Barrios-Rodriguez VD, Goncalves-Pereira J, Caviedes-Bucheli J. Determining factors in the success of direct pulp capping: A systematic review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2024; 25(4):392-401. [DOI:10.5005/jp-journals-10024-3673] [PMID]

- Alp Ş, Ulusoy N. Current approaches in pulp capping: A review. Cyprus J Med Sci. 2024; 9(3):154-60. [DOI:10.4274/cjms.2023.2022-37]

- Yavuz Y, Kotanli S, Dogan MS, Almak Z. Examination of 6 and 12 month follow-up of calcium hydroxide and calcium silicate materials used in direct and indirect pulp capping. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2025; 34(8):1289-98. [DOI:10.17219/acem/194504] [PMID]

- Goldberg M. Indirect versus direct pulp capping: Reactionary versus reparative dentin. J Dent Health Oral Disord Ther. 2019; 10(1):95-96. [DOI:10.15406/jdhodt.2019.10.00466]

- Boutsiouki C, Frankenberger R, Krämer N. Relative effectiveness of direct and indirect pulp capping in the primary dentition. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2018; 19(5):297-309. [DOI:10.1007/s40368-018-0360-x] [PMID]

- Cushley S, Duncan HF, Lappin MJ, Chua P, Elamin AD, Clarke M, et al. Efficacy of direct pulp capping for management of cariously exposed pulps in permanent teeth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Endod J. 2021; 54(4):556-71. [DOI:10.1111/iej.13449] [PMID]

- Hilton TJ, Ferracane JL, Mancl L. Northwest practice-based research collaborative in evidence-based dentistry (NWP). Comparison of CaOH with MTA for direct pulp capping: A PBRN randomized clinical trial. J Dent Res. 2013; 92(7 Suppl):16S-22S. [DOI:10.1177/0022034513484336] [PMID]

- Li Z, Cao L, Fan M, Xu Q. Direct pulp capping with calcium hydroxide or mineral trioxide aggregate: A meta-analysis. J Endod. 2015; 41(9):1412-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.joen.2015.04.012] [PMID]

- Paula AB, Laranjo M, Marto CM, Paulo S, Abrantes AM, Casalta-Lopes J, et al. Direct pulp capping: What is the most effective therapy? Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2018; 18(4):298-314. [DOI:10.1016/j.jebdp.2018.02.002] [PMID]

- Yoshida S, Sugii H, Itoyama T, Kadowaki M, Hasegawa D, Tomokiyo A, et al. Development of a novel direct dental pulp-capping material using 4-META/MMA-TBB resin with nano hydroxyapatite. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2021; 130:112426. [DOI:10.1016/j.msec.2021.112426] [PMID]

- Zaen El-Din AM, Hamama HH, Abo El-Elaa MA, Grawish ME, Mahmoud SH, Neelakantan P. The effect of four materials on direct pulp capping: An animal study. Aust Endod J. 2020; 46(2):249-56. [DOI:10.1111/aej.12400]

- Hatipoğlu Ö, Hatipoğlu FP, Javed MQ, Nijakowski K, Taha N, El-Saaidi C, et al. Factors affecting the decision-making of direct pulp capping procedures among dental practitioners: A multinational survey from 16 countries with meta-analysis. J Endod. 2023; 49(6):675-85. [DOI:10.1016/j.joen.2023.04.005] [PMID]

- Javed F, Kellesarian SV, Abduljabbar T, Gholamiazizi E, Feng C, Aldosary K, et al. Role of laser irradiation in direct pulp capping procedures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med Sci. 2017; 32(2):439-48. [DOI:10.1007/s10103-016-2077-6] [PMID]

- Deng Y, Zhu X, Zheng D, Yan P, Jiang H. Laser use in direct pulp capping: A meta-analysis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016; 147(12):935-42. [DOI:10.1016/j.adaj.2016.07.011] [PMID]

- Priya MS, Dakshindas DM, Warhadpande MM, Radke SA. Effectiveness of lasers in direct pulp capping among permanent teeth - A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Conserv Dent Endod. 2023; 26(5):494-501. [DOI:10.4103/jcd.jcd_344_23]

- Alsofi L, Khalil W, Binmadi NO, Al-Habib MA, Alharbi H. Pulpal and periapical tissue response after direct pulp capping with endosequence root repair material and low-level laser application. BMC Oral Health. 2022; 22(1):57. [DOI:10.1186/s12903-022-02099-0] [PMID]

- Alharbi H, Khalil W, Alsofi L, Binmadi N, Elnahas A. The effect of low-level laser on the quality of dentin barrier after capping with bioceramic material: A histomorphometric analysis. Aust Endod J. 2023; 49(1):27-37. [DOI:10.1111/aej.12610] [PMID]

- Al-Asmar AA, Abuarqoub D, Ababneh N, Jafar H, Zalloum S, Ismail M, et al. Potential effects of photobiomodulation therapy on human dental pulp stem cells. Appl Sci. 2024; 14(1):124. [DOI:10.3390/app14010124]

- Yazdanfar I, Barekatain M, Zare Jahromi M. Combination effects of diode laser and resin-modified tricalcium silicate on direct pulp capping treatment of caries exposures in permanent teeth: A randomized clinical trial. Lasers Med Sci. 2020; 35(8):1849-55. [DOI:10.1007/s10103-020-03052-9] [PMID]

- Ahmed AA, Farag MS, Fahmy OMI, Ghonaim AF. Clinical and radiographic assessment of diode laser 940 nm assisted direct pulp capping on dentin bridge formation versus the conventional method. Lasers in Dent Sci. 2024; 8(1):6. [DOI:10.1007/s41547-024-00210-y]

- Shbat L, Makhoul F, Kassis J. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of Ga-Al-As diode in immature permanent mandibular first molars direct pulp capping: A 12-month randomized controlled clinical trial. Endodontology. 2025; 37(1):16-22. [DOI:10.4103/endo.endo_54_24]

- Agrawal A, Varghese RK, Gupta NK, Choubey N, Dubey A, Priya S. In-vivo analysis of visible light cure calcium hydroxide, mineral trioxide aggregate and platelet-rich fibrin with and without laser therapy for direct pulp capping. Bioinformation. 2024; 20(9):1111. [DOI:10.6026/9732063002001111] [PMID]

- Priya MS, Dakshindas D, Warhandpande M, Dhobley A, Gosavi S, Wasule A, et al. Evaluation of histological response of human pulp to MTA as DPC agent with LLLT‐split mouth randomised controlled trial. Aust Endod J. 2025 [Unpublished]. [DOI:10.1111/aej.70023] [PMID]

- Rashmi K, Kumar NK, Kumar RM, Singh S, Brigit B, Shwetha R. A preliminary study on the effect of photobiomodulation with diode laser on direct pulp capping of cariously exposed teeth. J Conserv Dent Endod. 2025; 28(3):269-73. [DOI:10.4103/JCDE.JCDE_874_24] [PMID]

- Makkar S. A confocal laser scanning microscopic study evaluating the sealing ability of mineral trioxide aggregate, biodentine and a new pulp capping agent-theracal. Dent J Adv Stud. 2015; 3(1):20-5. [Link]

- Wang L, Liu C, Song Y, Wu F. The effect of low-level laser irradiation on the proliferation, osteogenesis, inflammatory reaction, and oxidative stress of human periodontal ligament stem cells under inflammatory conditions. Lasers Med Sci. 2022; 37(9):3591-9. [DOI:10.1007/s10103-022-03638-5] [PMID]

- Yoshida R, Kobayashi K, Onuma K, Yamamoto R, Chiba-Ohkuma R, Karakida T, et al. Enhancement of differentiation and mineralization of human dental pulp stem cells via TGF-β signaling in low-level laser therapy using Er:YAG lasers. J Oral Biosci. 2025; 67(1):100617. [DOI:10.1016/j.job.2025.100617] [PMID]

Type of Study: Review article |

Subject:

So on

Received: 2025/11/20 | Accepted: 2025/12/16 | Published: 2025/09/15

Received: 2025/11/20 | Accepted: 2025/12/16 | Published: 2025/09/15

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |