Sun, Feb 1, 2026

Volume 14, Issue 3 (9-2025)

2025, 14(3): 15-23 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Daryoush S, Falahchai M, Hemmati Y B. Future AI Models for Predicting Orthodontic Treatment Duration: Pathways, Challenges, and Innovations. Journal title 2025; 14 (3) :15-23

URL: http://3dj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-657-en.html

URL: http://3dj.gums.ac.ir/article-1-657-en.html

1- School of Dentistry, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

2- Department of Prosthodontics, Dental Sciences Research Center, School of Dentistry, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- Department of Orthodontics, Dental Sciences Research Center, School of Dentistry, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,Yasi.10482@gmail.com

2- Department of Prosthodontics, Dental Sciences Research Center, School of Dentistry, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- Department of Orthodontics, Dental Sciences Research Center, School of Dentistry, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 594 kb]

(15 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (186 Views)

Full-Text: (10 Views)

1. Introduction

The duration of orthodontic treatment is a significant concern for both dental clinicians and patients. Prolonged treatment can lead to clinical complications, such as development of white spot lesions, root resorption, reduced patient compliance, and increased treatment costs; while shorter and more predictable treatments increase patient satisfaction and efficiency (1). Estimating the duration of orthodontic treatment is complicated for dental clinicians, and conventional methods, including cephalometric analysis, diagnostic indices, and the dental clinicians’ experience with previous treatments, are often not sufficiently accurate (2). The multifactorial nature of treatment response is often not fully considered, including the type and severity of malocclusion, concomitant treatments with tooth extraction, proclination of mandibular anterior teeth, interdisciplinary approaches, such as orthognathic surgery, impacted teeth, and dentist’s experience. In addition, patient-related factors, such as age, regular attendance at treatment sessions, level of cooperation, and gender differences, have been reported to play a role in this regard (3-6).

Role of artificial intelligence (AI) in orthodontics

AI through machine learning (ML) and deep learning algorithms has recently shown promise in orthodontics, particularly in areas, such as automating cephalometric landmark identification (7), predicting the need for tooth extraction (8), and monitoring aligner treatment (9). However, only a few studies have directly addressed the prediction of treatment duration using AI, and their findings remain limited (10, 11). AI can use models to consider the influence of various factors and can also simultaneously use radiographs, photographs, and existing patient records, yielding higher accuracy.

Aim of the review

This review aimed to summarize the available evidence, critically assess methodological limitations, and outline future directions and necessary components. It also contributes to the development of clinically reliable AI models for predicting orthodontic treatment duration. The result of this further development is patient awareness of the approximate treatment duration before treatment, resulting in better cooperation, more accurate cost estimates, and consideration of different treatment plans based on estimated time and clinical complications.

Basics of AI in orthodontics (brief background)

AI refers to the ability of machines to exhibit intelligent behavior, primarily by learning from data to solve complex problems. ML, a subset of AI, allows systems to recognize patterns and make predictions based on data without direct human programming (12). ML in dentistry has primarily focused on predicting patient status by training models on previous data, as ML-based predictive models have shown higher accuracy than statistical models (13).

In orthodontics, AI applications have included the automatic identification of cephalometric landmarks, classification of dentomaxillofacial anomalies, prediction of the need for tooth extraction, and monitoring of aligner usage. These examples demonstrate the AI’s ability to manage complex diagnostic and therapeutic data (7, 8, 14). However, predicting treatment duration presents its own challenges, as it requires not only morphological assessment but also consideration of patient compliance, biological variation, and treatment mechanics (15). The following sections discuss the limited but growing evidence on the use of AI to predict treatment duration.

Studies related to AI and duration estimation

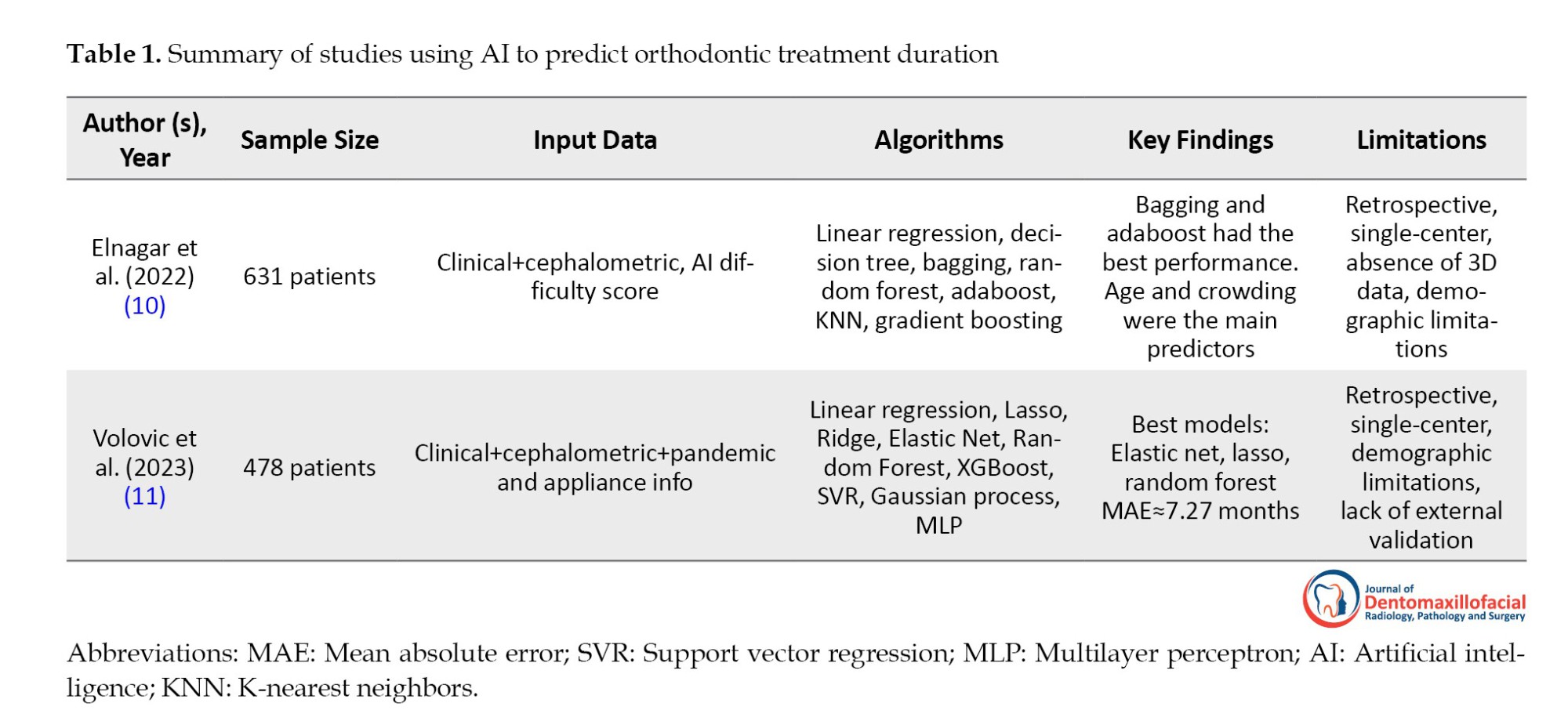

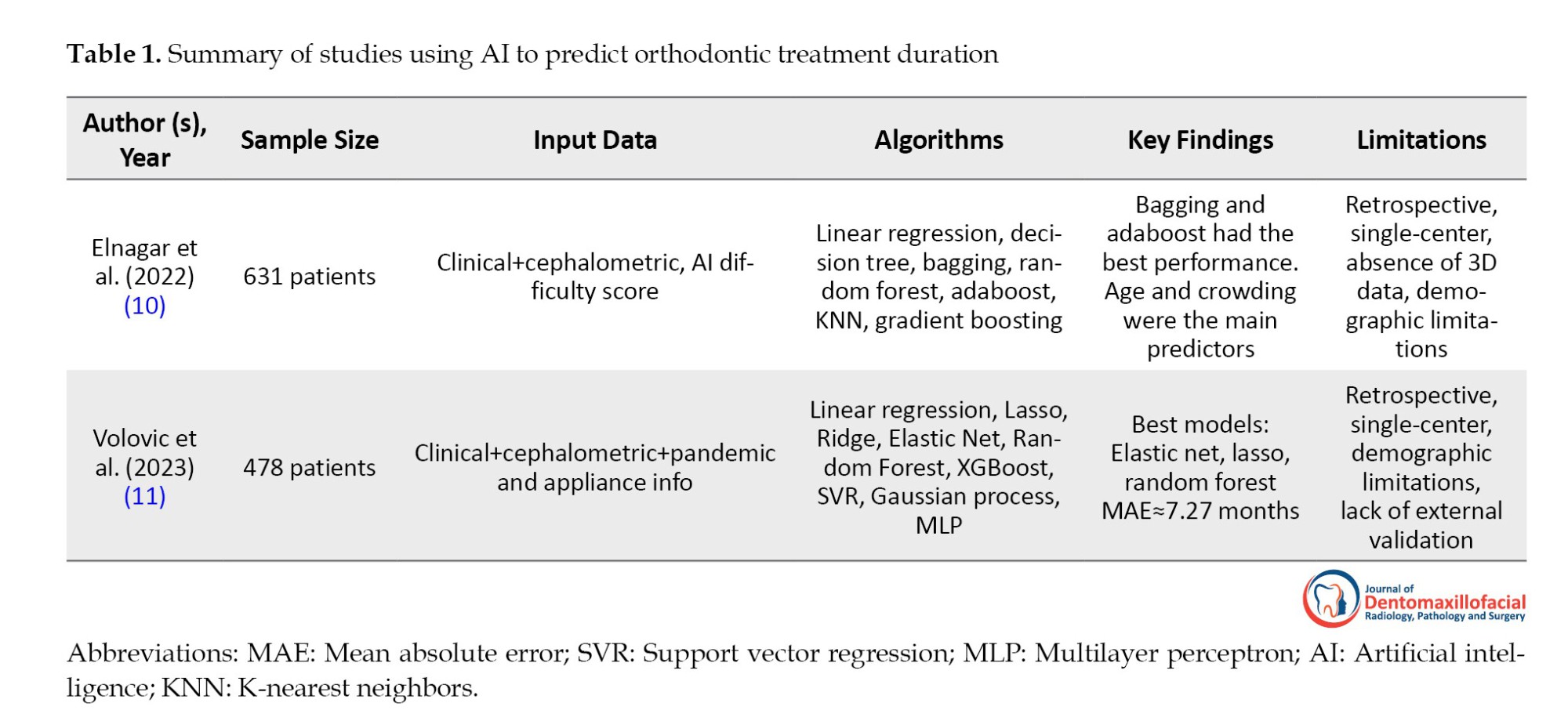

In study by Elnagar et al. (2022) (10), 631 orthodontic patients with complete treatment records treated by board-certified orthodontists were examined. Patient- and treatment-related parameters, including age, gender, crowding, overjet, overbite, and malocclusion type, were collected. Nine ML algorithms were tested, with Bagging and Adaboost showing the best prediction performance. The most important predictors were the patient’s age, level of crowding in the maxillary and mandibular arches, and overjet and overbite values. Adding AI-based difficulty scores improved the models’ accuracy. Overall, the ML models performed better than the orthodontists’ estimates, although there was a tendency to overestimate short treatments and underestimate long treatments (10).

Study of Volovic et al. (11) included 478 orthodontic patients who met strict inclusion criteria and had complete pre- and post-treatment records. Cephalometric data (31 landmarks and 46 variables), demographic information, treatment details, and factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and appliance type, were analyzed. Nine ML models were tested; among which, Lasso, Elastic Net, and random forest provided the best results. The decision to extract teeth, COVID-19 effects, and appliance type were the most crucial predictors. These models achieved a mean absolute error of 7.27 months, while orthodontists achieved ac9.66 months (equivalent to a 25% improvement).

Comparative critical analysis

Both studies showed that ML models can predict orthodontic treatment duration more accurately than experts. The study by Elnagar et al. (10) focused more on demographic and clinical variables without cephalometric data; while the study by Volovic et al. (11) included cephalometric data and treatment-environmental factors, such as COVID-19 and treatment appliances. In the study by Elnagar et al. (10), age and crowding were the most crucial predictors, while the study by Volovic et al. (11) reported greater importance of tooth extraction, appliance type, and the effects of COVID-19. Both studies showed similar bias in estimates (overestimating short treatments and underestimating long treatments). This similar bias could be due to the tendency of ML algorithms to minimize errors and to move predictions towards the mean of the data (16). This can cause shorter treatments to be longer than they actually are, and longer treatments to be shorter than they actually are. Also, variables, such as patient compliance and bracket debonding, which can alter treatment duration, were not considered. The use of limited single-center data may also be another cause of this bias. Overall, these findings demonstrate the great potential of ML, although current limitations remain. Table 1 summarizes a comparative overview of these studies, including their datasets, algorithms, key findings, and limitations

Related evidence (indirect contributions)

Although only a few studies have directly addressed the prediction of treatment duration, several AI-related applications have indirectly contributed to this field.

AI models related to tooth extraction

Since tooth extraction usually lengthens and complicates treatment, especially during space closure, a model that can predict this issue can serve as a key indicator in predicting treatment duration (17). In a related retrospective study by Leavitt et al. (8) in Indiana in 2023, the RF algorithm performed best in terms of overall accuracy. molar relationship, crowding of mandibular teeth, and overjet were identified as key predictors in the decision to extract teeth.

AI models related to facial profile changes

Models for predicting facial profile changes are also crucial because their data can be used to more accurately estimate treatment duration. In a study by Peng et al. (18) in Guangzhou in 2025, a three-layer artificial neural network model with error backpropagation was built to predict changes in the anterior teeth and profile view of 346 patients. In addition, the Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) method was used to identify significant predictors in each model.

AI models related to aligner treatment monitoring

Similarly, AI-based aligner treatment monitoring—often performed using time-of-use sensors—generates valuable behavioral data that can indicate the actual level of patient compliance and significantly increase the accuracy of treatment duration predictions (19). In a retrospective study by Manimegalan et al. (2015) (20) 40 patients undergoing clear aligner treatment were included in a 2025 study. Computerized monitoring significantly reduced the number of in-person appointments. The digitally monitored group showed higher patient satisfaction and compliance, underscoring the potential of tele-orthodontic treatment to improve access and increase treatment efficiency (20).

AI Models related to cephalometric image analysis

Models that analyze cephalometric images can provide more accurate, integrated image data for predictive models. In a study by Gao and Tang (7) in 2025, the authors introduced DeepFuse, a novel multimodal deep learning framework that integrates information from lateral cephalometry, cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), and digital dental models to simultaneously identify reference points and predict treatment outcomes. These side applications demonstrate the feasibility of integrating diverse data types and highlight methodological approaches transferable to the field of treatment duration prediction. In short, these factors, when combined together and as multi-modal data in AI models, can minimize prediction errors.

Limitations of current evidence

Existing research on AI-based orthodontic treatment duration prediction faces several significant limitations:

Reliance on retrospective, single-center data: Most current studies have collected data retrospectively and from a single treatment center. It means that the diversity of patients in terms of ethnicity, culture, lifestyle, and even treatment methods is limited, and the model cannot cover all different populations. Elnagar et al. (10) collected data from a teaching center in Chicago. In the study by Volovic et al. (11), samples were selected from a center in Indiana. Therefore, both studies only covered patients from the same region and cannot be generalized to other populations.

Small sample size and unbalanced distribution of treatment durations: When the number of patients is small or most patients have average treatment times, the ML model makes more predictions around the mean. This can lead to very short or very long treatments being underestimated. In the study by Elnager et al, (10) the number of patients was 631, which is a relatively good size but still small for complex algorithms. In the study by Volovic et al. (11), the number of patients was 478, which is smaller than that of Elnager et al. (10), and the distribution of treatment durations was skewed toward cases with average treatment times. Both studies reported that the models overestimated short treatments and underestimated long treatments.

Lack of external validation: When a model is trained and tested on a single center, it is unclear whether it will perform as well in other populations, and external validation with independent data is required to determine the robustness of the model (21). Both studies by Elnagar et al. (10) and Volovic et al. (11) used data from one single center. Neither model was tested on an external database. Therefore, it is unclear whether the accuracy would be maintained if the same models were run on other populations in other countries.

Limited focus on clinical and cephalometric features: Most studies only examined dento-skeletal factors or simple demographic information such as age and gender. However, other highly important factors, such as patient compliance, economic status, treatment motivation, bracket debonding, or even biological factors, such as bone density, were not included in the models. The study by Elnager et al. (10) included only simple clinical variables (age, gender, crowding, overjet, overbite, type of malocclusion) and an AI-based difficulty score, and no behavioral or biological data were included. Volovic et al. (11) included only two environmental factors, COVID-19 and appliance type, in addition to cephalometric and clinical data. However, variables, such as patient compliance or socioeconomic status, were absent.

Using complex and unexplainable models (black-box models): Algorithms, such as random forest, bagging, gradient boosting or neural networks, predict the final outcome or the duration of treatment, but no explanation is given as to why such a prediction was made, and this lack of transparency reduces the confidence of professionals because it is not clear on which factors the model is based on (22). In the study by Elnager et al. (10) Bagging and Adaboost performed best; both are black-box and their interpretation is not easy for clinicians. In the study by Volovic et al. (11), Elastic Net and Lasso were slightly more transparent because they had linear coefficients; however, more robust models, such as Random Forest, remained unexplainable. This makes orthodontists cautious in accepting these models for routine decision-making.

2. Future Directions

Essential components for robust models

To advance this field, future AI models for predicting orthodontic treatment duration should be developed on more diverse and representative data. The use of large, multicenter, and multiethnic cohorts can reduce bias and increase generalizability. It is equally important that inputs are designed to be multi-modal, including clinical data (such as malocclusion type and treatment mechanics), imaging data (including cephalometric, CBCT, and intraoral scans), behavioral variables (such as compliance and attendance), and biological markers (such as bone density or genetic factors).

Methodologically, hybrid approaches that combine classical ML with deep learning, especially in the form of adaptive or time-series models that update predictions over time, hold promise (23). Also, rigorous validation, including external testing and prospective cohorts, is essential to demonstrate reliability. For clinical use, future systems should be designed as user-friendly platforms that provide rapid predictions, facilitate clinical decision-making, and improve patient communication.

Considering the multifactorial nature of orthodontic treatment duration

Key factors influencing treatment duration remain controversial. For example, the relationship between treatment time and tooth extraction remains controversial: some studies have reported no significant effect, while more recent evidence suggests that treatments involving tooth extraction are more prolonged (17, 5).

Severity of malocclusion and case complexity have consistently been identified as strong predictors of longer treatment times. The American board of orthodontics discrepancy index (DI) also highly correlates with treatment duration: Cases with a DI≤15 typically last less than 22 months, while those with a DI>15 are significantly longer, often requiring more than 30 months (24).

Demographic factors, such as age and gender, have also been investigated, but with conflicting results. Biologically, increased age is associated with changes in tissue response to orthodontic forces: alveolar bone density increases, the periodontal ligament becomes more fibrotic, and the ability of periodontal and bone cells to proliferate and differentiate decreases. Younger patients often cooperate better, although some motivated older patients also show high cooperation. In terms of gender, treatment times have been consistently reported to be longer in males, possibly due to more missed treatment sessions (6). Treatment of impacted teeth, especially maxillary canines, takes significantly longer, and factors, such as age, gender, crown rotation, and morphological features (such as apical hook) influence outcomes (25). Psychosocial factors also play a role; for example, maternal emotional support has been shown to accelerate the duration of treatment, highlighting the importance of socioeconomic and psychological variables in addition to clinical predictors (26).

In addition to pretreatment factors, intra-treatment variables, such as patient compliance and appliance failures, such as bracket debonding, also have a significant impact on treatment duration (27). Understanding these factors can help design AI models that take into account the multifactorial nature of orthodontic treatment duration and provide more accurate predictions.

Designing multimodal research projects

Future studies on treatment duration estimation should adopt a multimodal approach to achieve greater accuracy. In addition to clinical and intra-treatment variables, radiographic imaging data and photographic records should also be included in the model.

1) Gao and Tang (7) conducted a multimodal study that combined lateral cephalometry, CBCT, and digital dental models to identify landmarks and predict orthodontic treatment outcomes; 2) Park et al. (28) also conducted a multimodal study using CBCT, information on dental changes, such as incisor position changes, and patient factors to develop a model to predict facial changes after orthodontic treatment.

These studies and their methodology can serve as a guide for the design of future studies on treatment duration prediction based on photographic images.

Using explainable AI (XAI) models

Most ML models used to predict orthodontic treatment duration, such as random forest, bagging, or neural networks, operate in a black-box fashion; that is, they provide a final prediction without explaining the decision-making process. This lack of transparency limits clinical adoption, as orthodontists need to know the factors involved in each prediction (22).

XAI frameworks can overcome this limitation. Tools, such as the SHAP values or permutation importance, show the contribution of each variable, such as age, crowding, overjet, or decision to extract teeth, to the final outcome. This transparency increases confidence in the models, as professionals can compare the results with their own clinical knowledge. Different XAI models can affect the accuracy of treatment duration estimates. The SHAP model shows the contribution of each variable, such as age, crowding, and tooth extraction, in predicting treatment duration. The local interpretable model-agnostic explanations model explains a specific prediction, for example, why a specific patient’s treatment duration was predicted to be 23 months. The counterfactual model shows how the outcome would change if conditions changed, for example, if the patient had been more cooperative, the treatment duration would have been 3 months shorter (29). In a study by Peng et al. (18), SHAP was used to determine the contribution of each variable in a model predicting changes in incisors and facial profile after orthodontic treatment.

XAI also has educational value and can help residents and less experienced specialists better understand the relative impact of different clinical factors. In addition, XAI allows for the identification of biases; for example, if a model disproportionately weights sensitive variables, such as gender or ethnicity, it can be corrected and used more accurately. Integrating XAI into clinical tools and applications can improve usability, such that systems not only predict treatment duration but also display key influencing factors in an interpretable manner. For example, if the predicted duration of the treatment is 28 months, the key influencing factors would severe crowding (+8 months), tooth extraction (+3 months), and older age (−2 months). Such a capability could improve clinical acceptance and patient communication.

Advanced modeling

In future studies, more advanced modeling can be used for more accurate results. Time-series models examine data over time so that the duration of orthodontic treatment is seen as a dynamic prediction that is updated with each visit. For example, in a study by Kwon et al. (30), a time-series model was used to predict skeletal and dental treatments. Adaptive models modify their predictions based on new data (e.g. changes in patient compliance or bracket debonding). For example, they simulate the biomechanical effects of orthodontic forces and allow for real-time optimization of bracket positions, aligner sequences, and force levels (31) as well as survival analysis, which is a statistical method used to predict the time of occurrence of an event. For example, Jin et al. (32) used survival analysis for orthodontic retainers.

Research roadmap

The path to researching a research topic usually involves three steps:

Phase I: Retrospective multi-modal data: Phase I is a study that collects retrospective data from multiple centers and integrates multi-source data, including clinical, cephalometric, CBCT, intraoral photographs, and behavioral data, to build an initial model on large and diverse data. In a study by Gao and Tang. (7), a multi-source deep learning framework called DeepFuse was introduced that combines information from lateral cephalograms, CBCT, and digital dental models to simulate tooth movement and predict treatment outcomes.

Phase II: Prospective, multi-center validation: The second phase is a prospective study with data collected from multiple centers in different countries, which increases ethnocultural diversity and reduces bias. This phase is critical for external validation and assessment of model stability. A study conducted in the UK by O'Brien et al. (33) (2009) evaluated the effectiveness of orthodontic and maxillofacial surgery treatments in 13 different clinics. This study was prospective and large-scale, and could provide a reasonable basis for the validation phase.

Phase III: Clinical integration in chairside tools: The third phase of the study is to integrate the model into clinical tools for use in the clinical setting. For example, software on a laptop or even an application (chairside tool) that allows the clinician to see the treatment duration prediction and influencing factors in real time, while consulting the patient. In a study by Li and Wang (2025) (29), a clinical decision support platform based on multi-task reinforcement learning and XAI for orthodontic treatments and maxillofacial surgery was introduced. This platform was designed for clinical integration and real-time decision support.

Clinical and ethical challenges

The use of AI in orthodontics presents several ethical challenges that must be addressed to ensure responsible and equitable use in the clinical setting.

Data privacy and security: Multimodal datasets—including radiographs, CBCT images, intraoral scans, photographic images, and behavioral data—are highly sensitive. The storage, transmission, and processing of these data must be in accordance with the international standards, such as the health insurance portability and accountability act or the general data protection regulation. The use of strong de-identification and encryption methods is essential to minimize the risk of patient re-identification (34).

Algorithmic bias: AI models trained on limited or homogeneous populations may perform poorly across ethnic, geographic, or socioeconomic groups. Such algorithmic bias can lead to unfair predictions. To mitigate this problem, it is necessary to have diverse data and use ethical AI techniques in developing and evaluating models.

Maintaining the role of clinical judgment: AI systems should act as decision support tools, not as a substitute for the orthodontist’s expertise. The ultimate responsibility for treatment decisions should still lie with the specialist to maintain patient safety, individualized treatment, and professional accountability.

Transparency and accountability: Complex, unexplainable (black-box) models pose challenges for transparency and accountability. The use of XAI frameworks can help professionals understand and validate predictions. In addition, clear guidelines are needed to determine liability in the event of errors, and the roles of developers, software vendors, and clinicians need to be defined. Addressing these ethical dimensions is critical to gaining the trust of professionals and patients and to ensuring safety and fairness in the clinical adoption of AI in orthodontics.

Conclusions

AI has shown significant potential for predicting orthodontic treatment duration and, in many cases, has been more accurate than estimates based on cephalometric analysis or experts’ clinical experience. Studies (10) and (11), have shown that ML models can predict average treatment duration with higher accuracy. However, patterns of bias still exist, with short treatments being overestimated and long treatments being underestimated. These limitations are mainly due to the use of retrospective and single-center data, limited sample sizes, and a focus on clinical and cephalometric variables; while behavioral, biological, and socioeconomic factors have been less considered. Despite these limitations, the findings suggest that the integration of AI-based predictive tools into orthodontics is feasible. Even rough estimates can help orthodontists improve communication with patients about treatment expectations, anticipate potential delays, and better plan appointments. It is crucial that this technology remains an adjunct and not a substitute for clinical judgment and experience. Transparent and explainable models are also critical for increasing professional confidence and clinical acceptance.

To advance this field, large multicenter, and multiethnic datasets that integrate multimodal variables, including imaging data, patient compliance indices, and biomarkers, are needed. Methodologically, adaptive and time-series-based models combined with XAI frameworks can increase the accuracy and dynamics of predictions and allow them to be updated throughout treatment. Finally, prospective validation and external testing are essential to transform experimental algorithms into reliable clinical tools. With these steps, AI can move from a research concept to a transformative tool in orthodontics, improving efficiency, patient satisfaction, and evidence-based decision-making.

Ethical Considerations

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors’ Contributions

Shima Daryoush: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Original draft Mehran Falahchai: Methodology, Investigation, Writing-Review and Editing Yasamin Babaee Hemmati: Investigation, Visualization, Writing-Review and Editing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht Iran.

References

The duration of orthodontic treatment is a significant concern for both dental clinicians and patients. Prolonged treatment can lead to clinical complications, such as development of white spot lesions, root resorption, reduced patient compliance, and increased treatment costs; while shorter and more predictable treatments increase patient satisfaction and efficiency (1). Estimating the duration of orthodontic treatment is complicated for dental clinicians, and conventional methods, including cephalometric analysis, diagnostic indices, and the dental clinicians’ experience with previous treatments, are often not sufficiently accurate (2). The multifactorial nature of treatment response is often not fully considered, including the type and severity of malocclusion, concomitant treatments with tooth extraction, proclination of mandibular anterior teeth, interdisciplinary approaches, such as orthognathic surgery, impacted teeth, and dentist’s experience. In addition, patient-related factors, such as age, regular attendance at treatment sessions, level of cooperation, and gender differences, have been reported to play a role in this regard (3-6).

Role of artificial intelligence (AI) in orthodontics

AI through machine learning (ML) and deep learning algorithms has recently shown promise in orthodontics, particularly in areas, such as automating cephalometric landmark identification (7), predicting the need for tooth extraction (8), and monitoring aligner treatment (9). However, only a few studies have directly addressed the prediction of treatment duration using AI, and their findings remain limited (10, 11). AI can use models to consider the influence of various factors and can also simultaneously use radiographs, photographs, and existing patient records, yielding higher accuracy.

Aim of the review

This review aimed to summarize the available evidence, critically assess methodological limitations, and outline future directions and necessary components. It also contributes to the development of clinically reliable AI models for predicting orthodontic treatment duration. The result of this further development is patient awareness of the approximate treatment duration before treatment, resulting in better cooperation, more accurate cost estimates, and consideration of different treatment plans based on estimated time and clinical complications.

Basics of AI in orthodontics (brief background)

AI refers to the ability of machines to exhibit intelligent behavior, primarily by learning from data to solve complex problems. ML, a subset of AI, allows systems to recognize patterns and make predictions based on data without direct human programming (12). ML in dentistry has primarily focused on predicting patient status by training models on previous data, as ML-based predictive models have shown higher accuracy than statistical models (13).

In orthodontics, AI applications have included the automatic identification of cephalometric landmarks, classification of dentomaxillofacial anomalies, prediction of the need for tooth extraction, and monitoring of aligner usage. These examples demonstrate the AI’s ability to manage complex diagnostic and therapeutic data (7, 8, 14). However, predicting treatment duration presents its own challenges, as it requires not only morphological assessment but also consideration of patient compliance, biological variation, and treatment mechanics (15). The following sections discuss the limited but growing evidence on the use of AI to predict treatment duration.

Studies related to AI and duration estimation

In study by Elnagar et al. (2022) (10), 631 orthodontic patients with complete treatment records treated by board-certified orthodontists were examined. Patient- and treatment-related parameters, including age, gender, crowding, overjet, overbite, and malocclusion type, were collected. Nine ML algorithms were tested, with Bagging and Adaboost showing the best prediction performance. The most important predictors were the patient’s age, level of crowding in the maxillary and mandibular arches, and overjet and overbite values. Adding AI-based difficulty scores improved the models’ accuracy. Overall, the ML models performed better than the orthodontists’ estimates, although there was a tendency to overestimate short treatments and underestimate long treatments (10).

Study of Volovic et al. (11) included 478 orthodontic patients who met strict inclusion criteria and had complete pre- and post-treatment records. Cephalometric data (31 landmarks and 46 variables), demographic information, treatment details, and factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and appliance type, were analyzed. Nine ML models were tested; among which, Lasso, Elastic Net, and random forest provided the best results. The decision to extract teeth, COVID-19 effects, and appliance type were the most crucial predictors. These models achieved a mean absolute error of 7.27 months, while orthodontists achieved ac9.66 months (equivalent to a 25% improvement).

Comparative critical analysis

Both studies showed that ML models can predict orthodontic treatment duration more accurately than experts. The study by Elnagar et al. (10) focused more on demographic and clinical variables without cephalometric data; while the study by Volovic et al. (11) included cephalometric data and treatment-environmental factors, such as COVID-19 and treatment appliances. In the study by Elnagar et al. (10), age and crowding were the most crucial predictors, while the study by Volovic et al. (11) reported greater importance of tooth extraction, appliance type, and the effects of COVID-19. Both studies showed similar bias in estimates (overestimating short treatments and underestimating long treatments). This similar bias could be due to the tendency of ML algorithms to minimize errors and to move predictions towards the mean of the data (16). This can cause shorter treatments to be longer than they actually are, and longer treatments to be shorter than they actually are. Also, variables, such as patient compliance and bracket debonding, which can alter treatment duration, were not considered. The use of limited single-center data may also be another cause of this bias. Overall, these findings demonstrate the great potential of ML, although current limitations remain. Table 1 summarizes a comparative overview of these studies, including their datasets, algorithms, key findings, and limitations

Related evidence (indirect contributions)

Although only a few studies have directly addressed the prediction of treatment duration, several AI-related applications have indirectly contributed to this field.

AI models related to tooth extraction

Since tooth extraction usually lengthens and complicates treatment, especially during space closure, a model that can predict this issue can serve as a key indicator in predicting treatment duration (17). In a related retrospective study by Leavitt et al. (8) in Indiana in 2023, the RF algorithm performed best in terms of overall accuracy. molar relationship, crowding of mandibular teeth, and overjet were identified as key predictors in the decision to extract teeth.

AI models related to facial profile changes

Models for predicting facial profile changes are also crucial because their data can be used to more accurately estimate treatment duration. In a study by Peng et al. (18) in Guangzhou in 2025, a three-layer artificial neural network model with error backpropagation was built to predict changes in the anterior teeth and profile view of 346 patients. In addition, the Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) method was used to identify significant predictors in each model.

AI models related to aligner treatment monitoring

Similarly, AI-based aligner treatment monitoring—often performed using time-of-use sensors—generates valuable behavioral data that can indicate the actual level of patient compliance and significantly increase the accuracy of treatment duration predictions (19). In a retrospective study by Manimegalan et al. (2015) (20) 40 patients undergoing clear aligner treatment were included in a 2025 study. Computerized monitoring significantly reduced the number of in-person appointments. The digitally monitored group showed higher patient satisfaction and compliance, underscoring the potential of tele-orthodontic treatment to improve access and increase treatment efficiency (20).

AI Models related to cephalometric image analysis

Models that analyze cephalometric images can provide more accurate, integrated image data for predictive models. In a study by Gao and Tang (7) in 2025, the authors introduced DeepFuse, a novel multimodal deep learning framework that integrates information from lateral cephalometry, cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), and digital dental models to simultaneously identify reference points and predict treatment outcomes. These side applications demonstrate the feasibility of integrating diverse data types and highlight methodological approaches transferable to the field of treatment duration prediction. In short, these factors, when combined together and as multi-modal data in AI models, can minimize prediction errors.

Limitations of current evidence

Existing research on AI-based orthodontic treatment duration prediction faces several significant limitations:

Reliance on retrospective, single-center data: Most current studies have collected data retrospectively and from a single treatment center. It means that the diversity of patients in terms of ethnicity, culture, lifestyle, and even treatment methods is limited, and the model cannot cover all different populations. Elnagar et al. (10) collected data from a teaching center in Chicago. In the study by Volovic et al. (11), samples were selected from a center in Indiana. Therefore, both studies only covered patients from the same region and cannot be generalized to other populations.

Small sample size and unbalanced distribution of treatment durations: When the number of patients is small or most patients have average treatment times, the ML model makes more predictions around the mean. This can lead to very short or very long treatments being underestimated. In the study by Elnager et al, (10) the number of patients was 631, which is a relatively good size but still small for complex algorithms. In the study by Volovic et al. (11), the number of patients was 478, which is smaller than that of Elnager et al. (10), and the distribution of treatment durations was skewed toward cases with average treatment times. Both studies reported that the models overestimated short treatments and underestimated long treatments.

Lack of external validation: When a model is trained and tested on a single center, it is unclear whether it will perform as well in other populations, and external validation with independent data is required to determine the robustness of the model (21). Both studies by Elnagar et al. (10) and Volovic et al. (11) used data from one single center. Neither model was tested on an external database. Therefore, it is unclear whether the accuracy would be maintained if the same models were run on other populations in other countries.

Limited focus on clinical and cephalometric features: Most studies only examined dento-skeletal factors or simple demographic information such as age and gender. However, other highly important factors, such as patient compliance, economic status, treatment motivation, bracket debonding, or even biological factors, such as bone density, were not included in the models. The study by Elnager et al. (10) included only simple clinical variables (age, gender, crowding, overjet, overbite, type of malocclusion) and an AI-based difficulty score, and no behavioral or biological data were included. Volovic et al. (11) included only two environmental factors, COVID-19 and appliance type, in addition to cephalometric and clinical data. However, variables, such as patient compliance or socioeconomic status, were absent.

Using complex and unexplainable models (black-box models): Algorithms, such as random forest, bagging, gradient boosting or neural networks, predict the final outcome or the duration of treatment, but no explanation is given as to why such a prediction was made, and this lack of transparency reduces the confidence of professionals because it is not clear on which factors the model is based on (22). In the study by Elnager et al. (10) Bagging and Adaboost performed best; both are black-box and their interpretation is not easy for clinicians. In the study by Volovic et al. (11), Elastic Net and Lasso were slightly more transparent because they had linear coefficients; however, more robust models, such as Random Forest, remained unexplainable. This makes orthodontists cautious in accepting these models for routine decision-making.

2. Future Directions

Essential components for robust models

To advance this field, future AI models for predicting orthodontic treatment duration should be developed on more diverse and representative data. The use of large, multicenter, and multiethnic cohorts can reduce bias and increase generalizability. It is equally important that inputs are designed to be multi-modal, including clinical data (such as malocclusion type and treatment mechanics), imaging data (including cephalometric, CBCT, and intraoral scans), behavioral variables (such as compliance and attendance), and biological markers (such as bone density or genetic factors).

Methodologically, hybrid approaches that combine classical ML with deep learning, especially in the form of adaptive or time-series models that update predictions over time, hold promise (23). Also, rigorous validation, including external testing and prospective cohorts, is essential to demonstrate reliability. For clinical use, future systems should be designed as user-friendly platforms that provide rapid predictions, facilitate clinical decision-making, and improve patient communication.

Considering the multifactorial nature of orthodontic treatment duration

Key factors influencing treatment duration remain controversial. For example, the relationship between treatment time and tooth extraction remains controversial: some studies have reported no significant effect, while more recent evidence suggests that treatments involving tooth extraction are more prolonged (17, 5).

Severity of malocclusion and case complexity have consistently been identified as strong predictors of longer treatment times. The American board of orthodontics discrepancy index (DI) also highly correlates with treatment duration: Cases with a DI≤15 typically last less than 22 months, while those with a DI>15 are significantly longer, often requiring more than 30 months (24).

Demographic factors, such as age and gender, have also been investigated, but with conflicting results. Biologically, increased age is associated with changes in tissue response to orthodontic forces: alveolar bone density increases, the periodontal ligament becomes more fibrotic, and the ability of periodontal and bone cells to proliferate and differentiate decreases. Younger patients often cooperate better, although some motivated older patients also show high cooperation. In terms of gender, treatment times have been consistently reported to be longer in males, possibly due to more missed treatment sessions (6). Treatment of impacted teeth, especially maxillary canines, takes significantly longer, and factors, such as age, gender, crown rotation, and morphological features (such as apical hook) influence outcomes (25). Psychosocial factors also play a role; for example, maternal emotional support has been shown to accelerate the duration of treatment, highlighting the importance of socioeconomic and psychological variables in addition to clinical predictors (26).

In addition to pretreatment factors, intra-treatment variables, such as patient compliance and appliance failures, such as bracket debonding, also have a significant impact on treatment duration (27). Understanding these factors can help design AI models that take into account the multifactorial nature of orthodontic treatment duration and provide more accurate predictions.

Designing multimodal research projects

Future studies on treatment duration estimation should adopt a multimodal approach to achieve greater accuracy. In addition to clinical and intra-treatment variables, radiographic imaging data and photographic records should also be included in the model.

1) Gao and Tang (7) conducted a multimodal study that combined lateral cephalometry, CBCT, and digital dental models to identify landmarks and predict orthodontic treatment outcomes; 2) Park et al. (28) also conducted a multimodal study using CBCT, information on dental changes, such as incisor position changes, and patient factors to develop a model to predict facial changes after orthodontic treatment.

These studies and their methodology can serve as a guide for the design of future studies on treatment duration prediction based on photographic images.

Using explainable AI (XAI) models

Most ML models used to predict orthodontic treatment duration, such as random forest, bagging, or neural networks, operate in a black-box fashion; that is, they provide a final prediction without explaining the decision-making process. This lack of transparency limits clinical adoption, as orthodontists need to know the factors involved in each prediction (22).

XAI frameworks can overcome this limitation. Tools, such as the SHAP values or permutation importance, show the contribution of each variable, such as age, crowding, overjet, or decision to extract teeth, to the final outcome. This transparency increases confidence in the models, as professionals can compare the results with their own clinical knowledge. Different XAI models can affect the accuracy of treatment duration estimates. The SHAP model shows the contribution of each variable, such as age, crowding, and tooth extraction, in predicting treatment duration. The local interpretable model-agnostic explanations model explains a specific prediction, for example, why a specific patient’s treatment duration was predicted to be 23 months. The counterfactual model shows how the outcome would change if conditions changed, for example, if the patient had been more cooperative, the treatment duration would have been 3 months shorter (29). In a study by Peng et al. (18), SHAP was used to determine the contribution of each variable in a model predicting changes in incisors and facial profile after orthodontic treatment.

XAI also has educational value and can help residents and less experienced specialists better understand the relative impact of different clinical factors. In addition, XAI allows for the identification of biases; for example, if a model disproportionately weights sensitive variables, such as gender or ethnicity, it can be corrected and used more accurately. Integrating XAI into clinical tools and applications can improve usability, such that systems not only predict treatment duration but also display key influencing factors in an interpretable manner. For example, if the predicted duration of the treatment is 28 months, the key influencing factors would severe crowding (+8 months), tooth extraction (+3 months), and older age (−2 months). Such a capability could improve clinical acceptance and patient communication.

Advanced modeling

In future studies, more advanced modeling can be used for more accurate results. Time-series models examine data over time so that the duration of orthodontic treatment is seen as a dynamic prediction that is updated with each visit. For example, in a study by Kwon et al. (30), a time-series model was used to predict skeletal and dental treatments. Adaptive models modify their predictions based on new data (e.g. changes in patient compliance or bracket debonding). For example, they simulate the biomechanical effects of orthodontic forces and allow for real-time optimization of bracket positions, aligner sequences, and force levels (31) as well as survival analysis, which is a statistical method used to predict the time of occurrence of an event. For example, Jin et al. (32) used survival analysis for orthodontic retainers.

Research roadmap

The path to researching a research topic usually involves three steps:

Phase I: Retrospective multi-modal data: Phase I is a study that collects retrospective data from multiple centers and integrates multi-source data, including clinical, cephalometric, CBCT, intraoral photographs, and behavioral data, to build an initial model on large and diverse data. In a study by Gao and Tang. (7), a multi-source deep learning framework called DeepFuse was introduced that combines information from lateral cephalograms, CBCT, and digital dental models to simulate tooth movement and predict treatment outcomes.

Phase II: Prospective, multi-center validation: The second phase is a prospective study with data collected from multiple centers in different countries, which increases ethnocultural diversity and reduces bias. This phase is critical for external validation and assessment of model stability. A study conducted in the UK by O'Brien et al. (33) (2009) evaluated the effectiveness of orthodontic and maxillofacial surgery treatments in 13 different clinics. This study was prospective and large-scale, and could provide a reasonable basis for the validation phase.

Phase III: Clinical integration in chairside tools: The third phase of the study is to integrate the model into clinical tools for use in the clinical setting. For example, software on a laptop or even an application (chairside tool) that allows the clinician to see the treatment duration prediction and influencing factors in real time, while consulting the patient. In a study by Li and Wang (2025) (29), a clinical decision support platform based on multi-task reinforcement learning and XAI for orthodontic treatments and maxillofacial surgery was introduced. This platform was designed for clinical integration and real-time decision support.

Clinical and ethical challenges

The use of AI in orthodontics presents several ethical challenges that must be addressed to ensure responsible and equitable use in the clinical setting.

Data privacy and security: Multimodal datasets—including radiographs, CBCT images, intraoral scans, photographic images, and behavioral data—are highly sensitive. The storage, transmission, and processing of these data must be in accordance with the international standards, such as the health insurance portability and accountability act or the general data protection regulation. The use of strong de-identification and encryption methods is essential to minimize the risk of patient re-identification (34).

Algorithmic bias: AI models trained on limited or homogeneous populations may perform poorly across ethnic, geographic, or socioeconomic groups. Such algorithmic bias can lead to unfair predictions. To mitigate this problem, it is necessary to have diverse data and use ethical AI techniques in developing and evaluating models.

Maintaining the role of clinical judgment: AI systems should act as decision support tools, not as a substitute for the orthodontist’s expertise. The ultimate responsibility for treatment decisions should still lie with the specialist to maintain patient safety, individualized treatment, and professional accountability.

Transparency and accountability: Complex, unexplainable (black-box) models pose challenges for transparency and accountability. The use of XAI frameworks can help professionals understand and validate predictions. In addition, clear guidelines are needed to determine liability in the event of errors, and the roles of developers, software vendors, and clinicians need to be defined. Addressing these ethical dimensions is critical to gaining the trust of professionals and patients and to ensuring safety and fairness in the clinical adoption of AI in orthodontics.

Conclusions

AI has shown significant potential for predicting orthodontic treatment duration and, in many cases, has been more accurate than estimates based on cephalometric analysis or experts’ clinical experience. Studies (10) and (11), have shown that ML models can predict average treatment duration with higher accuracy. However, patterns of bias still exist, with short treatments being overestimated and long treatments being underestimated. These limitations are mainly due to the use of retrospective and single-center data, limited sample sizes, and a focus on clinical and cephalometric variables; while behavioral, biological, and socioeconomic factors have been less considered. Despite these limitations, the findings suggest that the integration of AI-based predictive tools into orthodontics is feasible. Even rough estimates can help orthodontists improve communication with patients about treatment expectations, anticipate potential delays, and better plan appointments. It is crucial that this technology remains an adjunct and not a substitute for clinical judgment and experience. Transparent and explainable models are also critical for increasing professional confidence and clinical acceptance.

To advance this field, large multicenter, and multiethnic datasets that integrate multimodal variables, including imaging data, patient compliance indices, and biomarkers, are needed. Methodologically, adaptive and time-series-based models combined with XAI frameworks can increase the accuracy and dynamics of predictions and allow them to be updated throughout treatment. Finally, prospective validation and external testing are essential to transform experimental algorithms into reliable clinical tools. With these steps, AI can move from a research concept to a transformative tool in orthodontics, improving efficiency, patient satisfaction, and evidence-based decision-making.

Ethical Considerations

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors’ Contributions

Shima Daryoush: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Original draft Mehran Falahchai: Methodology, Investigation, Writing-Review and Editing Yasamin Babaee Hemmati: Investigation, Visualization, Writing-Review and Editing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht Iran.

References

- Shi X, Wu B, Cao D, Liu J, Qian X, Liu M, et al. Effect of socioeconomic and malocclusion-related factors on duration of orthodontic treatment by fixed appliance: A retrospective study. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2023; 26(4):650-659. [DOI:10.1111/ocr.12661] [PMID]

- Smołka P, Nelke K, Struzik N, Wiśniewska K, Kiryk S, Kensy J, et al. Discrepancies in cephalometric analysis results between orthodontists and radiologists and artificial intelligence: A systematic review. Appl Sci. 2024; 14(12):4972. [DOI:10.3390/app14124972]

- Tsichlaki A, Chin SY, Pandis N, Fleming PS. How long does treatment with fixed orthodontic appliances last? A systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2016; 149(3):308-18. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.09.020] [PMID]

- Faruqui S, Fida M, Shaikh A. Factors affecting treatment duration-A dilemma in orthodontics. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2018; 30(1):16-21. [PMID]

- Mavreas D, Athanasiou AE. Factors affecting the duration of orthodontic treatment: A systematic review. Eur J Orthod. 2008; 30(4):386-95. [DOI:10.1093/ejo/cjn018] [PMID]

- Prasad S, Farella M. Speed limits to orthodontic treatment: A review. NZ Dent J. 2021; 117:113-25. [Link]

- Gao F, Tang Y. Multimodal deep learning for cephalometric landmark detection and treatment prediction. Sci Rep. 2025; 15(1):25205. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-025-06229-w] [PMID]

- Leavitt L, Volovic J, Steinhauer L, Mason T, Eckert G, Dean JA, et al. Can we predict orthodontic extraction patterns by using machine learning? Orthod Craniofac Res. 2023; 26(4):552-9. [DOI:10.1111/ocr.12641] [PMID]

- Caruso S, Caruso S, Pellegrino M, Skafi R, Nota A, Tecco S. A knowledge-based algorithm for automatic monitoring of orthodontic treatment: The dental monitoring system. Two Cases. Sensors. 2021; 21(5):1856. [DOI:10.3390/s21051856] [PMID]

- Elnagar MH, Pan AY, Handono A, Sanchez F, Talaat S, Bourauel C, et al. Utilization of machine learning methods for predicting orthodontic treatment length. Oral. 2022; 2(4):263-73. [DOI:10.3390/oral2040025]

- Volovic J, Badirli S, Ahmad S, Leavitt L, Mason T, Bhamidipalli SS, et al. a novel machine learning model for predicting orthodontic treatment duration. Diagnostics. 2023; 13(17):2740.[DOI:10.3390/diagnostics13172740] [PMID]

- Khanagar SB, Al-Ehaideb A, Maganur PC, Vishwanathaiah S, Patil S, Baeshen HA, et al. Developments, application, and performance of artificial intelligence in dentistry-A systematic review. J Dent Sci. 2021; 16(1):508-522. [DOI:10.1016/j.jds.2020.06.019] [PMID]

- Bichu YM, Hansa I, Bichu AY, Premjani P, Flores-Mir C, Vaid NR. Applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning in orthodontics: A scoping review. Prog Orthod. 2021; 22(1):18. [DOI:10.1186/s40510-021-00361-9] [PMID]

- Paddenberg-Schubert E, Midlej K, Krohn S, Schröder A, Awadi O, Masarwa S, et al. Machine learning models for improving the diagnosing efficiency of skeletal class I and III in German orthodontic patients. Sci Rep. 2025; 15(1):12738. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-025-97717-6] [PMID]

- Melo ACEO, Carneiro LO, Pontes LF, Cecim RL, Mattos JNR, Normando D. Factors related to orthodontic treatment time in adult patients. Dental Press J Orthod. 2013; 18:59-63. [DOI: 10.1590/s2176-94512013000500011] [PMID]

- James G, Witten D, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. An introduction to statistical learning: With applications in R. New York: Springer; 2013. [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4614-7138-7]

- Elias KG, Sivamurthy G, Bearn DR. Extraction vs nonextraction orthodontic treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Angle Orthod. 2024; 94(1):83-106. [DOI:10.2319/021123-98.1] [PMID]

- Peng J, Zhang Y, Zheng M, Wu Y, Deng G, Lyu J, et al. Predicting changes of incisor and facial profile following orthodontic treatment: A machine learning approach. Head Face Med. 2025; 21(1):22. [DOI:10.1186/s13005-025-00499-5] [PMID]

- Ferlito T, Hsiou D, Hargett K, Herzog C, Bachour P, Katebi N, et al. Assessment of artificial intelligence-based remote monitoring of clear aligner therapy: A prospective study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2023; 164(2):194-200. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajodo.2022.11.020] [PMID]

- Manimegalan P, Pragnya B, Jain M, Tomy M, Chinnappa V, Ashwathi N. Digital orthodontic treatment monitoring and remote aligner therapy: A paradigm change in contemporary orthodontics. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2025; 17(Suppl 3):S2623-5. [DOI:10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_788_25]

- Steyerberg EW. Study design for prediction modeling. In: Steyerberg EW, editor. Clinical prediction models: A practical approach to development, validation, and updating. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-16399-0_3]

- Guidotti R, Monreale A, Ruggieri S, Turini F, Giannotti F, Pedreschi D. A survey of methods for explaining black box models. ACM Comput Surv. 2018; 51(5):1-42. [DOI:10.1145/3236009]

- Auconi P, Gili T, Capuani S, Saccucci M, Caldarelli G, Polimeni A, et al. The validity of machine learning procedures in orthodontics: What is still missing? J Pers Med. 2022; 12(6):957. [DOI:10.3390/jpm12060957] [PMID]

- Mitwally RA, Alesawi LM, Arishi TQ, Humedi AY, Al Baaltahin SS, Saeedi YA, et al. Factors affecting orthodontic treatment time and how to predict it. Int J Commun Med Public Health. 2022; 9(1):1-5. [DOI:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20214798]

- Goh PKT, Pulemotov A, Nguyen H, Pinto N, Olive R. Treatment duration by morphology and location of impacted maxillary canines: A cone-beam computed tomography investigation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2024; 166(2):160-70. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajodo.2024.04.010] [PMID]

- Nakhleh K, Joury E, Dean R, Marcenes W, Johal A. Can socioeconomic and psychosocial factors predict the duration of orthodontic treatment? Eur J Orthod. 2020; 42(3):263-9. [DOI:10.1093/ejo/cjz074] [PMID]

- Jung MH. Factors influencing treatment efficiency. Angle Orthod. 2021 1; 91(1):1-8. [DOI:10.2319/050220-379.1] [PMID]

- Park YS, Choi JH, Kim Y, Choi SH, Lee JH, Kim KH, et al. Deep learning-based prediction of the 3D postorthodontic facial changes. J Dent Res. 2022; 101(11):1372-9. [DOI:10.1177/00220345221106676] [PMID]

- Li Z, Wang L. Multi-task reinforcement learning and explainable AI-driven platform for personalized planning and clinical decision support in orthodontic-orthognathic treatment. Sci Rep. 2025; 15(1):24502. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-025-09236-z] [PMID]

- Kwon SW, Moon JK, Song SC, Cha JY, Kim YW, Choi YJ, et al. Time-series X-ray image prediction of dental skeleton treatment progress via neural networks. Comput Biol Med. 2025; 196(Pt B):110799. [DOI:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2025.110799] [PMID]

- Guo X, Shao Y. AI-driven dynamic orthodontic treatment management: personalized progress tracking and adjustments-a narrative review. Front Dent Med. 2025; 6:1612441. [DOI:10.3389/fdmed.2025.1612441] [PMID]

- Jin C, Bennani F, Gray A, Farella M, Mei L. Survival analysis of orthodontic retainers. Eur J Orthod. 2018; 40(5):531-6. [DOI:10.1093/ejo/cjx100] [PMID]

- O'Brien K, Wright J, Conboy F, Appelbe P, Bearn D, Caldwell S, et al. Prospective, multi-center study of the effectiveness of orthodontic/orthognathic surgery care in the United Kingdom. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009; 135(6):709-14. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.10.043] [PMID]

- Ahmed A, Shahzad A, Naseem A, Ali S, Ahmad I. Evaluating the effectiveness of data governance frameworks in ensuring security and privacy of healthcare data: A quantitative analysis of ISO standards, GDPR, and HIPAA in blockchain technology. Plos One. 2025; 20(5):e0324285. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0324285] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original article |

Subject:

Radiology

Received: 2025/09/14 | Accepted: 2025/11/15 | Published: 2025/09/15

Received: 2025/09/14 | Accepted: 2025/11/15 | Published: 2025/09/15

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |